Benjamin D. Adapon, MD, graduated from the University of the Philippines – College of Medicine in 1958. He went to the USA for further training, as a Rotating Intern in Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, and as an Assistant Resident in Medicine at Mt. Sinai Hospital in Cleveland, Ohio.

He, then, took up residency in Radiology at New York University Hospital in 1960. His training included courses in isotopes and radiation therapy. By 1965, he completed his Fellowship in Neuroradiology at the New York University Hospital, sponsored by the U.S. National Institutes of Health of Bethesda, Maryland.

Neuroradiology is not just like general practice… You cannot guess – you have to know it.”

Asked why he chose to take up Neuroradiology, Dr. Adapon replied by giving us a picture of the medical scene during his time. “When I graduated 52 years ago, the most glamorous of subspecialties in medicine were those of the internists and the surgeons, including the ophthalmologists.” He had planned to take up one of these courses, but, as fate would have it, he chose to walk the path less traveled. Dr. Adapon had simply tagged along with a friend to a talk given by Dr. Juan Taveras, now regarded as the “Father of Neuroradiology”, about the newest advances in the field of neuroradiology. Who knew that just a few years later he would become one of Dr. Taveras’ best protégés and colleagues?

“Neuroradiology is not just like general practice, where you are successful when you have narrowed down so many differential diagnoses. You cannot guess – you have to know it. It is a question of being very specific.” As an example, Dr. Adapon recalls a case he just saw the day before – that of an intracranial tumor – which he correctly called as surgical despite opposing opinions from various specialties.

This has actually been a pattern. A large part of his practice consists of problematic cases of patients who have been referred to him for second opinions from all over the country (including regional consults from Guam, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Hong Kong and China). He vividly tells stories from years passed and his amazingly detailed recall of how he managed his many cases confirms for you that he is one of the best around.

Dr. Adapon was part of a hallowed group of doctors in New York who blazed a quiet revolution in medicine with the rise of radiology, particularly of neuroradiological angiography, pneumoencephalography and myelography, as an important part of modern healthcare. Led by Dr. Juan Taveras and Dr. Norman Chase of Columbia-Presbyterian and NYU Medical Center, Dr. Adapon considers his time with them as being “trained by the gods”.

“Neuroradiology probably started about 50 years ago. And, because of neuroradiology, there was a tremendous advancement in neuroscience, particularly neurology and neurosurgery. Before [then] we only [could talk] of the theoretical – theoretical lesions in the brain and spinal cord – but now we are sure.”

Up to today, Dr. Adapon is the only Filipino neuroradiologist in the country certified by the American Society of Neuroradiology. He is well-known by colleagues, especially in his field, and is duly well-recognized when attending annual gatherings and conventions. He established the specialization in the country with the founding of the Philippine Society of Neuroradiology, and established the country’s first Stroke Center in 1998 involved in the therapeutic interventions of acute and chronic stroke and its related cases. To date, he has trained numerous individuals, all leaders in the field of radiology.

It was Dr. Adapon who introduced computerized tomography scanning (CT scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to the Philippines.

Dr. Adapon was a senior fellow in Neuroradiology when he once gave a talk in the 1970’s to the PGH faculty, consisting mostly of neurosurgeons and neurologists, about the advances in the field of radiology. “They were behind the times,” he remembers. “It used to be that there was an 80% chance of mortality when patients would undergo neurosurgical operations at that time.” That was when he knew he had to return to the Philippines and help develop the medical practice there. “Dr. Manahan came to me five times asking me to please come down here and help them.” Another respected colleague, a member of the Rockefeller Foundation, which was then funding medical institutions in Asia (including the UP College of Medicine) through the China Medical Board, also convinced him to bring his practice to the Philippines and the rest of the Orient. At that time, he became the only neuroradiologist in the entire region.

He returned via the Balik Scientist program in December 1977 and promptly was recognized as a Phase II Awardee of the National Science & Development Board of the Philippines. “It was 1973 or 1974 when CT scanning came out,” he recalls, “We had our first CT scan here [in Makati Medical Center] in 1978.” That was the first CT scan in Southeast Asia.

The introduction of the CT technology marked a new era in the field of medicine because its innovation introduced different, up-to-date diagnostic and therapeutic modalities. Dr. Adapon was responsible for many firsts in Philippine medicine, including the first intravenous percutaneous radiologic embolizations of extracranial facial AVMs and hemangiomas, among others, in 1979; the first CT-guided aspiration biopsy of the spine in 1979 and of intra-axial CNS tumors and masses of lungs, kidneys, and the pancreas in 1980; the first CT-guided operative biopsy of a CNS tumor in 1980; the first selective arterial catheter insufflation of chemotherapeutic agents into the liver and head malignancies; the first stroke intervention via intra-arterial angio-guided thrombolysis; and the first embolization of an aneurysm via the balloon-assisted technique, and many more.

He also introduced the many machines used in neuroradiology in the country today, including the first operational MRI in May 1989, the first high-field superconductive MRI scanner on June 1993, the first 16-multislice CT scanner in 2002, and the first 64-multislice CT scanner in 2005.

And he is a proud member of the Phi Kappa Mu, currently nearing 60 years as a Loyal Son of the Fraternity.

The PHIs were the important and respected ones. They were the leaders and revolutionaries. They were the doers and achievers in class!

Asked why he joined Phi he answered, “Well, I am a go getter acheter kamagra oral jelly pas cher. You know, only tough guys join the Phi. I selected Phi because it was more exclusive and more difficult.” One of the lessons that he learned when joining the Fraternity was that overcoming such difficulties were critical to succeed and belong. “The Phis were known as the macho guys. As it was difficult getting in, we felt like we [became] the anointed ones after the process!”

“I joined the group [who were] active in the class. We all decided that we are all going to Phi,” Dr. Adapon recalls of his time in the College of Medicine. “The Phis were the important and respected ones. They were the leaders and revolutionaries. They were the doers and achievers in class!” As an example, Dr. Adapon cited how Tito Gatmaitan, his classmate and his batch’s Superior Exemplar, was the medical board exams topnotcher in 1958. Despite the seemingly high expectations, he beams at remembering how his time in the College was made more memorable by Phi. “Malakas kami uminom noon! Kami ang mga marunong mag-enjoy!” (“We were strong drinkers! We were the ones who knew how to enjoy!”)

Well, I am a go getter. You know, only tough guys join the Phi. I selected Phi because it was more exclusive and more difficult.”

Dr. Adapon acknowledges how the Fraternity has helped him in recent years. “When I find out that (a certain person) was a Phi, I feel as if we knew each other for so long!” In Manhattan, when he still resided there, he would host the brods at gatherings . “The camaraderie, closeness, and immediate recognition are trademarks of being brothers in Phi. You can talk to or ask a brod anything!” Being brods made everyone more approachable, and he readily recalls being able to interact closely with esteemed brothers, including Dr. Alendry Caviles Φ ’49 and Dr. Benny Agbayani Φ ‘54, among many others.

Brod Ben Adapon sharing stories with Brod Peping Eustaquio ’37 at the Fraternity’s 80th Anniversary Dinner.

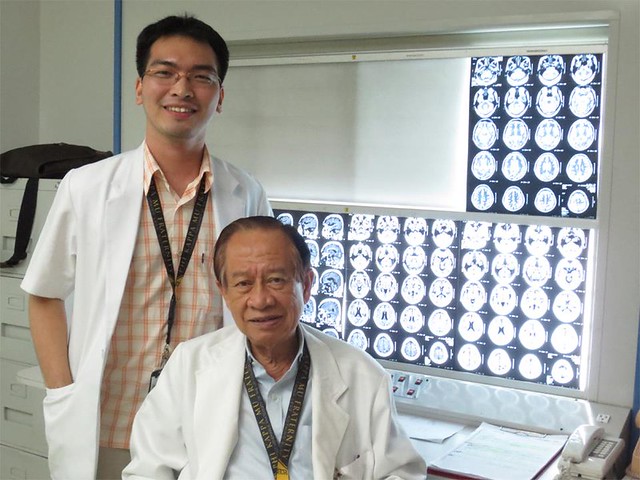

Paying it forward, he readily mentors younger brods who seek his help and advice. One particular brod is Dr. Ronnie Baticulon Φ ’03, a neurosurgeon-in-training at UP-PGH, who occasionally visits Dr. Adapon for life lessons in between a discourse on reading cranial CT plates and managing patients. The lanyard he wears daily was a token of gratitude from Dr. Baticulon. “I am proud to say that much of what I know about the brain, I will always owe to my mentor and brod, Dr. Ben Adapon,” Dr. Baticulon admits.

Ronnie Baticulon ’03 proudly professes that he owes much of his knowledge about the brain to Brod Ben Adapon.

More than half a decade as a Phi, Dr. Adapon has no second thoughts about joining the Fold. “It was worth it. There are no regrets.”

Hard work has been instrumental on how he was able to succeed in his chosen vocation. “Let’s try to do the best work we can do, not just do it,” he advises. “Whatever I do, I try to do my best. If the Philippines will only do it (this way), we will surpass our neighbors. Let us not settle for second best.”

Radiology, being a study of the definite of which commitment to a diagnosis is of paramount value, taught him life lessons as well. His advice for students is this: “Do a good job, be reasonable and make a stand. Don’t be indefinite.”

Do a good job, be reasonable and make a stand. Don’t be indefinite.

—

Credits to Mr. R. Augusto Adapon and Dr. P. Henry Adapon, MD